Research

Long-Term Research Agenda and Motivation

My long-term research agenda seeks to understand how animals navigate, learn and adapt in dynamic landscapes, building predictive frameworks that link environmental change to behavioral decision-making and migration resilience, an urgent challenge underscored by recent advances in movement and climate adaptation studies. Across ecosystems, animals encounter regions of dynamic permeability, such as thawing lakes, snow-covered terrain, where movement costs fluctuate over time. My ultimate goal is to bridge behavioral ecology and environmental dynamics by developing mechanistic, data-driven models that translate individual decision-making into population-scale patterns of migration resilience.

My central question is:

How do dynamic landscape features shape animal movement and decision-making?

This question has guided my research from early investigations of migratory connectivity to my current and future work on how animals perceive and learn about changing environments. By integrating long-term GPS tracking, remote-sensing imagery, and movement modeling, I examine how external cues and internal processes interact to shape navigation strategies across spatial and temporal scales. This interdisciplinary approach enables ecological questions about migration to be addressed through measurable behavioral patterns, translating environmental variability into quantifiable movement responses.

Dynamic Lake Ice Conditions Shape Caribou Water-Crossing Behavior in the Arctic

A central challenge in movement ecology is to understand how animals navigate transient, fine-scale landscape barriers in dynamic environments. In the rapidly warming Arctic, once-stable frozen lakes and rivers, long used as seasonal corridors, are becoming unreliable, yet their behavioral consequences remain poorly quantified.

Caribou and reindeer (both Rangifer tarandus), keystone migratory ungulates that travel up to 1000 km annually across frozen lakes and rivers, exemplify this challenge. The dramatic population collapse of the Bathurst herd, from ~480,000 individuals in the 1980s to fewer than 7,000 today, underscores the urgency of understanding how shifting ice phenology affects migratory behavior. This ecological crisis and broader knowledge gap motivated my Ph.D. research, which linked satellite-derived measures of lake-ice dynamics to GPS-tracked caribou movements, providing one of the first quantitative frameworks for connecting fine-scale ice phenology with individual decision-making during migration.

At Contwoyto Lake, a >100 km glacial lake in northern Canada, I integrated two decades (2001–2021) of GPS tracking data from 406 adult barren-ground caribou with daily MODIS albedo imagery to build a scalable, remote-sensing framework for quantifying lake-ice dynamics. Using a percentile-based normalization of each pixel’s annual albedo trajectory, I captured the full seasonal progression of ice formation and melt (except for polar nights) and aligned it with the timing of animal movements. This daily alignment allowed behavioral responses, crossing versus circumnavigating, to be analyzed at the same temporal resolution as environmental change.

Our results reveal a clear seasonal shift in behavioral drivers: in spring, crossing behavior was best predicted by intermediate-scale ice conditions (along the potential crossing path), with a behavioral threshold at the 56th percentile of annual albedo values, while in fall, movement-based metrics such as speed ratios better explained decisions. This suggests that caribou perceive and evaluate environmental resistance over spatial windows that match specific behavioral tasks, rather than at pixel-level or whole-lake scales, offering a concrete entry point for modeling perceptual range in migratory systems.

This percentile-based, daily-albedo framework links remote-sensing dynamics with animal decision-making at an unprecedented temporal resolution, striking a balance between spatial detail, temporal frequency, and historical depth, surpassing prior methods limited by coarse revisit rates, short time spans, or lack of within-lake heterogeneity. Conceptually, the study reframed lake ice as a seasonal behavioral filter, rather than a static obstacle, that modulates functional connectivity across Arctic landscapes. Practically, the crossing-probability thresholds identified here provide rare mechanistic indicators to help quantify early-stage migratory disruptions and offer insight into the mechanisms of movement resilience and plasticity. Although developed for Arctic caribou, the framework is transferable to any system where animals confront dynamic barriers, establishing the foundation for my subsequent research on perception and experience in animal movement.

Publication:

Liao, Qianru, Eliezer Gurarie, and William F. Fagan. "Dynamic Lake Ice Conditions Shape Caribou Water-Crossing Behavior in the Arctic." bioRxiv (2025): 2025-09. In revision

Media & News:

Yale Climate Connections – “Climate change is forcing pregnant caribou to make

dangerous decisions”

New Phytologist Foundation: 2025 New Phytologist Award for Graduate Student Presentation

Ongoing: Migration Network Dynamics and Long-Term Connectivity

My current work is to understand the structural organization and long-term dynamics of migration of caribou. Using three decades of GPS data from 12 caribou herds in northwestern Canada (>1,600 individuals), I am constructing multi-decadal “trail maps” that visualize where migratory routes concentrate, diverge, or disappear. By comparing routes across years, I detect the emergence and erosion of connectivity corridors shaped by both behavioral memory and environmental change.

To achieve this, I apply quantitative measures of trajectory similarity and clustering to examine migration across multiple hierarchical levels. At the individual level, pairwise similarity matrices quantify route fidelity; at the subgroup level, clustering analyses detect recurring travel groups and test their stability across years; and at the herd level, I evaluate whether migration networks maintain cohesion or fragment over time, revealing potential links to climate-driven changes in ice and snow regimes.

Preliminary results show a remarkable convergence onto favored travel corridors, suggesting potential memory effects or shared experiential pathways within herds. Together, these analyses provide a new quantitative lens on how collective experience and environmental dynamics interact to shape migratory networks, forming the analytical foundation for my future cross-system research.

Findings:

1) the structure inherent in a set of routes 2) change over time in a set of routes. In Prep.

Intraspecific Encounters Can Lead to Reduced Range Overlap

In this study, we explore the impact of direct encounters between animals, focusing on how proximity influences their spatial behavior over time. Leveraging high-resolution movement data, we examined whether close encounters between species like coyotes (Canis latrans) and grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) lead to changes in their range distributions.

Our findings show that such encounters can indeed prompt long-term, large-scale shifts in space use, likely as a strategy to reduce conflict. By analyzing coyote data, we observed a significant reduction in home range overlap after one individual altered its movement following an encounter. Similarly, with grizzly bears, we found that significant changes in range distribution overlap occurred when females with cubs were involved in encounters during late fall. We also demonstrated that using smaller spatial thresholds to define encounters led to more frequent and pronounced changes in range distribution overlap.

This research underscores the value of encounter-based analyses in understanding animal behavior and space use. It also highlights how statistical methods for population-level home range analysis can be repurposed to assess the long-term consequences of these encounters.

Publication:

Fagan, W.F., Krishnan, A., Liao, Q. et al. Intraspecific encounters can lead to reduced range overlap. Movement Ecology 12, 58 (2024). (Joint second author)

Wild canids and felids differ in their reliance on reused travel routeways

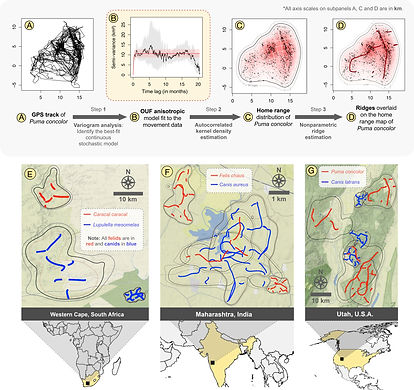

Understanding how animals use space is fundamental to ecology, evolution, and conservation. Our study examines how mammalian carnivores organize their movements within home ranges, focusing on their reliance on repeatedly used travel routeways—paths that animals follow regularly but not identically. By analyzing GPS movement data from over 1,200 individuals across 34 species of canids and felids worldwide, we found striking differences between the two clades. Canids, on average, exhibited higher routeway density and greater reuse intensity than felids, suggesting that spatial behavior reflects both ecological and evolutionary processes.

These findings challenge long-standing assumptions of spatial homogeneity in predator-prey models and highlight how behavioral heterogeneity influences encounters, foraging, and conservation outcomes for large carnivores globally.

Publication:

Fagan, W.F., ..., Liao, Q.,...et al. Wild canids and felids differ in their reliance on reused travel routes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122 (40) (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2401042122.